In many discussions of sustainability, the assumption is made that the distant past and the distant future have no direct relevance to the immediate present. This assumption is not unreasonable since ripples from the past often do die out by the time they reach the present; similarly events in the present generate ripples that often die out if we wait a sufficiently long time. There must be some basis for our belief that events can be considered unconnected. We capture that belief in the use of probability as a means to predict the future: Bayesian probability.

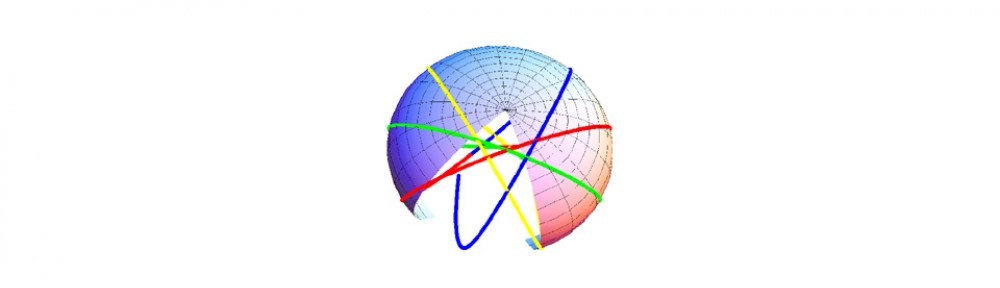

I argue that this assumption is incorrect. See Geometry, Language and Strategy, Thomas, 2006, World Scientific (New York). There are longterm cyclic effects that originate in the past, whose effects don’t die out. Some events from the present will continue on into the future without appreciable damping. The justification for this argument is as common sense as the above assumption. We see boom and bust cycles in market behaviors; we see the longterm consequences of global wars. The appeal of the above assumption is its simplicity, not its accuracy. I argue that if we had a theory that took into account such longterm cycles, we would consider that theory superior. We would see choices fluctuate according to both the short-term and long-term cycles (e.g. the following CDF figure based on an attack-defense model, chapter 9 of the dynamics of decision processes illustrates choice behavior with two cycles; the CDF format is not yet supported on smart phones, sorry).

[WolframCDF source=”http://decisionprocesstheory.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Two-cycle-strategies.cdf” width=”328″ height=”334″ altimage=”http://decisionprocesstheory.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Two-cycle-strategies.cdf”]

An attribute we would look for in a more complete explanation of events would be that longterm cycles, though hard to see (weakly coupled to our observations), can have very strong effects (payoffs). This would contrast with our experiences of the day-to-day short cycle time events that are easy to see (strongly coupled to our observations), but with relatively weak effects (payoffs).

How would this view change our understanding of sustainability? We might then understand that as human beings we make small changes (weak coupling) to our environment that over a long time cycle time can have strong effects (payoffs). Because we have been successful in the past to accommodate environmental changes is no guarantee that we will be as successful in the future.